original pastime

In 1885, bicycles took the shape of the diamond, a look and utility not much unlike the bicycles we ride today. They were labeled the safety bicycle, and having evolved from the high-wheeler, were awarded this name for good reason. By 1890, twenty-seven bicycle manufacturers in the United States recognized the trendiness of this safer alternative, becoming focused on what they believed to be the future of cycling.

In September of that year, Robert M. Keating would join the show, crafting his version of the ultimate bicycle and The Keating Wheel Company was born.

The years to follow are known as the Gilded-Age of cycling. The bicycle becoming a transformational force for change in nineteenth-century American society, much in the way the personal computer changed the fabric of the twentieth. Cheaper than a horse, and providing more freedom than a train, human beings were able to go faster and further afield than ever before. In 1896, Scientific American wrote:

"As a social revolutionizer it has never had an equal. It has put the human race on wheels, and has changed many of the most ordinary processes and methods of social life."

At its peak in popularity, it was a catalyst for uniting the wildly disconnected post-Civil War society of America, one that was tightly structured around gender, race and wealth. It would bring rise to Marshall "Major" Taylor, the cycling prodigy who would become the first black international superstar and second black world champion in any sport in United States history. It would assist in the development of the “modern woman”, particularly by lifting women out of the clutches of Victorian custom and values. In a New York World interview, Susan B. Anthony proclaimed:

"Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel ... the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood."

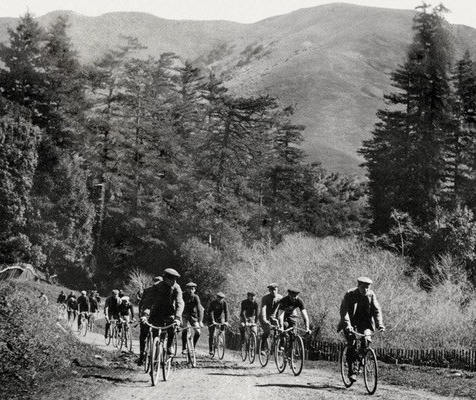

By 1900, cycling had become America’s favorite pastime as both sport and recreation, sharing the top spot with baseball. The deadly but popular 6-day track races would lead to endurance rides pushing hundreds of miles. The roads that made up these popular cycling routes became the focus of improvement, and farmers built stands along them offering food and refreshment - a precursor to modern day rest-areas. In fact, the first freeway built in the western United States linked Los Angeles and Pasadena. Constructed in 1900, it began as an elevated bike path originally known as the California Cycleway.

For Keating, this tremendous rise in popularity allowed him to build an impressive following for his bicycles which stretched as far away as Australia and New Zealand.

Domestically, his bicycles would go on to take state and world records in races across Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, California and Georgia. And it was atop his machines that two riders claimed the record for a ride between Boston and Chicago.

With the breakneck pace and ever increasing range of cycling came a natural, albeit exponential growth in the technology behind it. Bicycle manufacturing became a fertile seedbed for invention, freeing technical and mechanical entrepreneurs with vision and skills to stretch the envelope of nineteenth and early-twentieth-century manufacturing processes and factory design.

Indeed, the bicycle’s DNA is embedded within the evolution of the automobile, motorcycle and airplane; a bicycle chain propelled the first Ford automobile and the first Wright Brothers’ airplane was conceived and built in their bicycle shop.

It was the electric vehicle that Keating began developing in 1899, and later his motorcycle in 1900 that provide insight into just how forward-thinking he truly was. Positioned towards urban markets, Keating's vehicle was a godsend to early delivery businesses. Proven to climb grades up to 35%, it could travel a distance of 45 miles on a single 55-minute charge, and even utilized a power controller that flipped the motors into reverse on the downhills, effectively recharging the onboard batteries. (Crazy as it may seem, Tesla and its modern vehicles are based on one-hundred-year-old tech.)

Keating's motorcycle was first seen in a patent drawing filed June 18, 1900, which he quickly followed with several others. These evolving patents would become the industry standard in the pioneering days of American motorcycle manufacturing, and were ultimately replicated later by Harley-Davidson and Indian. So much so in fact that R.M. Keating would take both manufacturers to court for patent infringement, winning both settlements.

Keating and his wheel company offer a unique peak at this formative time in the nation's industrial history. As bicycle fanatics and as Keating's, my family and I have undertaken its resurrection, and with it, Keating's first new bicycle in over a century.

Historical reference: Keating, R. K. Wheel Man: Robert M. Keating, pioneer of bicycles, motorcycles and automobiles. McFarland, 2014.